Enforcing Stormwater Permits Along the Mystic River with Google Street View

In 2015 the New America Foundation asked me and Shannon Dosemagen to write a chapter for their Drone Primer on the politics of mapping and surveillance. I worked in an example of positive citizen surveillance by the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) that I’d heard about in a session at the 2015 Public Interest Environmental Law Conference. I’ve excerpted and adapted my writeup of the CLF case as a stand-alone article here.

Geo-tagged aerial and street-level imagery on the web can be a boon to both environmental lawyers and the small teams of regulators tasked by US states with enforcing the Clean Water Act. Flyovers and street patrols through industrial and residential districts can be conducted rapidly and virtually, looking for clues to where the runoff in rivers is coming from. Combining aerial and street-level photographs with searchable public permitting data, the 1972 Clean Water act’s stormwater regulations are now more enforceable in practice than they have ever been (Alsentzer et. al. 2015).

State and federal environmental agencies often do not have time or resources to adequately enforce permits under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) that regulates construction and industrial stormwater runoff, and roughly half of facilities violate their stormwater permits every year (Russell and Duhigg 2009). Enforcement can be picked up by third parties, however, because NPDES permits are public. Plaintiff groups and legal teams conduct third-party enforcement through warnings and lawsuit filings. Legal settlements from lawsuits recoup the plaintiffs legal costs, and can also include fines whose funds are directed towards community-controlled Supplemental Environmental Projects that help improve environmental conditions in the violator’s watershed. The Conservation Law Foundation (CLF), a Boston-based policy and legal non-profit, operates in precisely this manner, recouping their costs through lawsuits and directing funds to Supplemental Environmental Projects in the Mystic River Watershed.

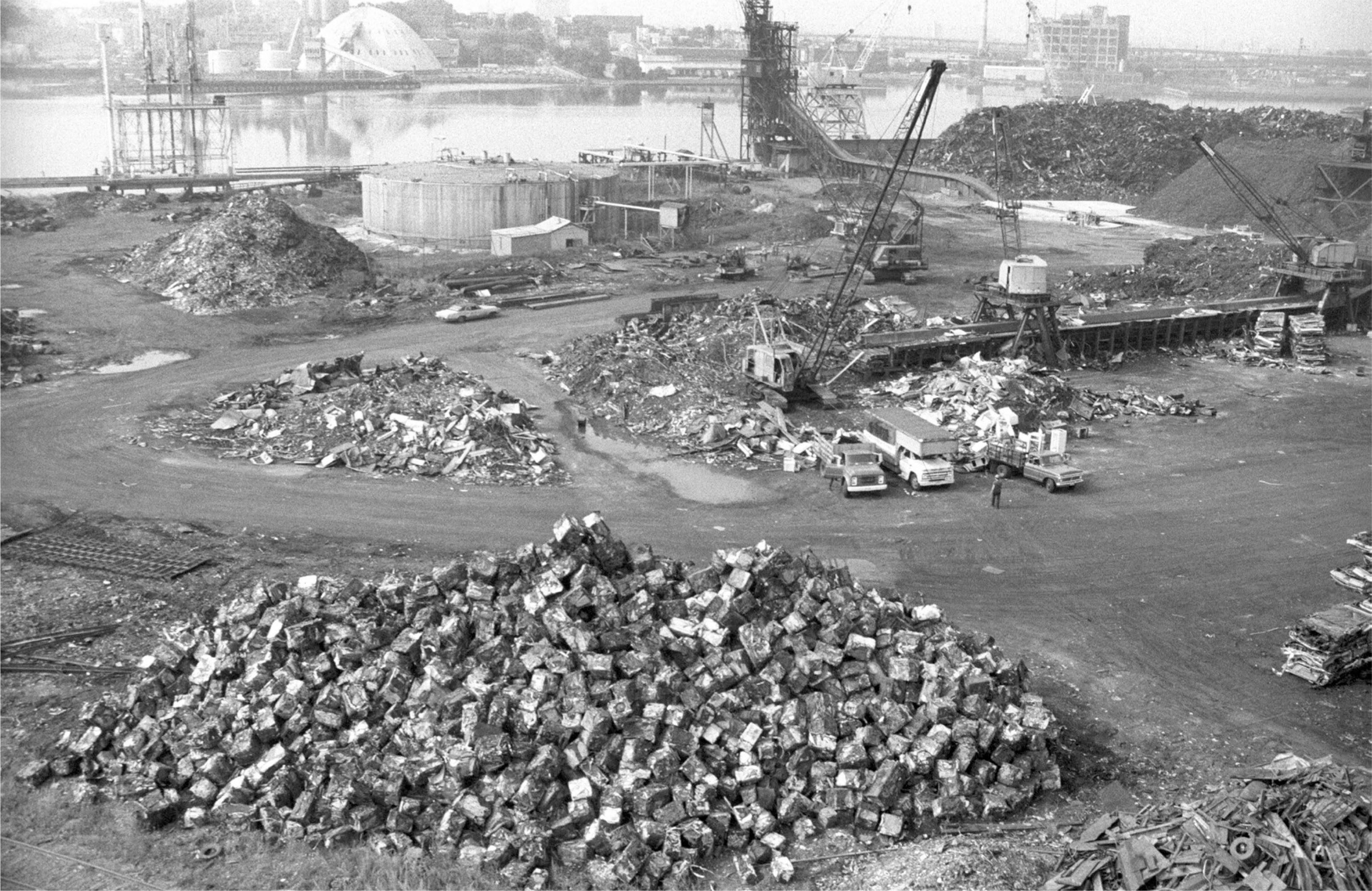

In 2010 a neighborhood group approached the CLF about a scrap metal facility on the Mystic River. Observable runoff demonstrated the facility had never built a stormwater system, and a quick US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) NPDES permit search revealed that they had never applied for or received a permit. The facility was flying under the EPA’s enforcement radar, and so were four of the facility’s neighbors.

Between 2010 and 2015 CLF’s environmental lawyers initiated 45 noncompliance cases by looking for industrial facilities along waterfronts in Google Street View, and then searching the EPA’s stormwater permit database for the facility’s address. Most complaints are resolved through negotiated settlement agreements, where the facility owner or operator funds Supplemental Environmental Projects for river restoration, public education, and water quality monitoring that can catch other water quality criminals. Together, CLF and a coalition of partners such as the Mystic River Watershed Association are creating a steady stream of revenue for restoration, education, and engagement in the environmental health of one of America’s earliest industrial waterways.

Regardless of their effect, legal threats are stressful, often expensive, and can take years to resolve. Even when threatened polluters are acting in good faith to clean up their systems, the process of identifying and persuading companies to comply with environmental regulations can strain relationships in communities. Non-compliant small businesses on the Mystic River that have been in operation since before the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972 may never have been alerted to their obligations under the law. Their absence from the EPA database reflects mutual ignorance from bureaucrats of businesses and businesses of bureaucracy. However, businesses bear the direct costs of installed equipment, staff time, and facility downtime, indirect costs to professional reputation from delayed operations or identification as a polluter, and transactional costs of paying for legal assistance or court fees. Indirect and transactional costs are hidden punishments that can accrue regardless of guilt or readiness to comply.

To combat the negative perceptions that can arise from the use of legal threats, CLF proactively works to fit itself into a community-centered watershed management strategy. CLF and their partners run public education and outreach campaigns and start with issuing warnings that aren’t court-filed (Alsentzer et. al., 2015). Identifying and working with businesses operating in good faith is a tenet of community-based restoration efforts. By using courts as a last resort and participating in public processes where citizens can express the complexity of their landscape relationships, CLF and their partners are increasing participation in environmental decision-making and establishing the legitimacy of restoration and enforcement decisions.

Regulations and permit databases can often be tough to put to work, but the CLF’s case was fairly straightforward: they simply searched for company’s addresses in a publicly available database. We would love to hear cases of more groups using this approach or other simple modes of regulatory engagement.

Header Image: Scrap Yard on the Mystic River, Spencer Grant 1974, Getty Images CC-BY.

Sources and Further Reading:

Alsentzer, Guy, Zak Griefen, and Jack Tuholske. 2015. CWA Permitting & Impaired Waterways. Panel session at the Public Interest Environmental Law Conference, University of Oregon.

Conservation Law Foundation Newsletter “Coming Clean”, Winter 2014;

D.C. Denison, “Conservation Law Foundation suing alleged polluters”, Boston Globe, May 10, 2012.

Russell, Karl and Charles Duhigg, Clean Water Act Violations are Neglected at a Cost of Suffering. In The New York Times, Sept 12, 2009. Part of the Toxic Waters Series

Archived 4th of March 2018 from Publiclab.org.