Solar Thermal Atmospheric Research Station (STARS) Proposals, 1978-1982

In the early 1960s, Buckminster Fuller did back-of-the-envelope calculations for a giant, solar-heated balloon that he called Cloud Nine. This 1-mile (1.6km) diameter rigid geodesic sphere could, he claimed, house thousands.

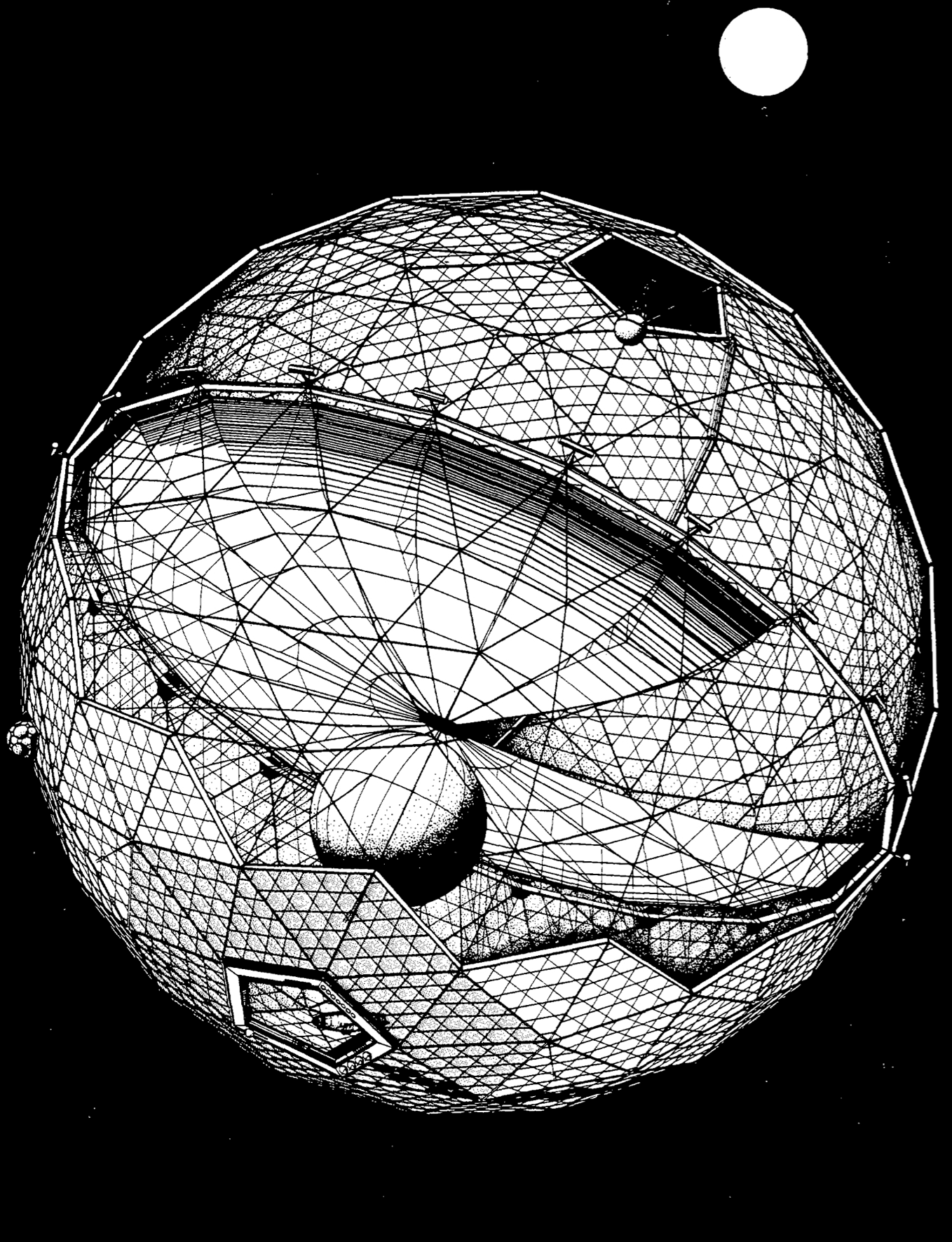

Project for Floating Cloud Structures (Cloud Nine). R. Buckminster Fuller and Soji Sadao

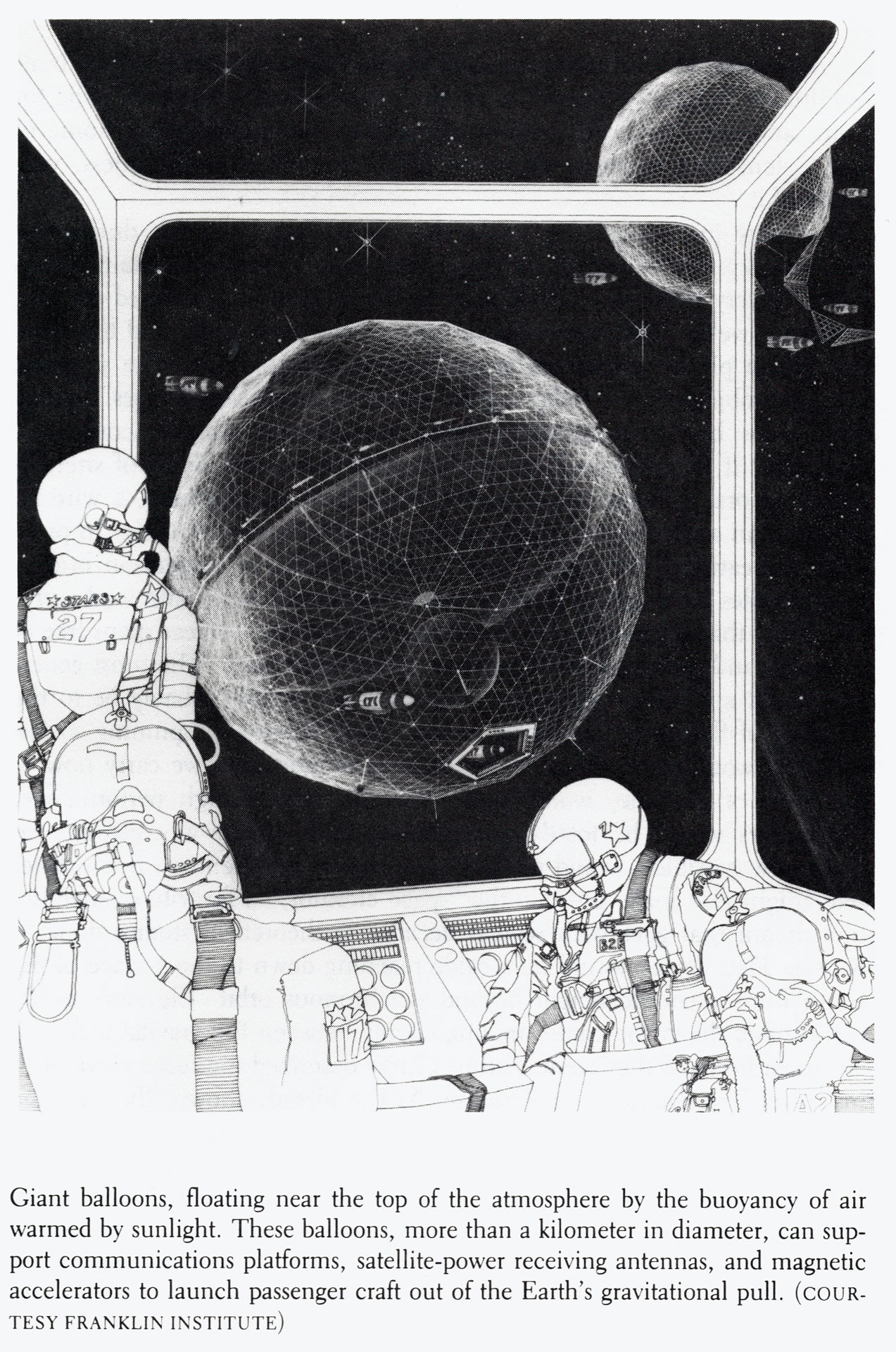

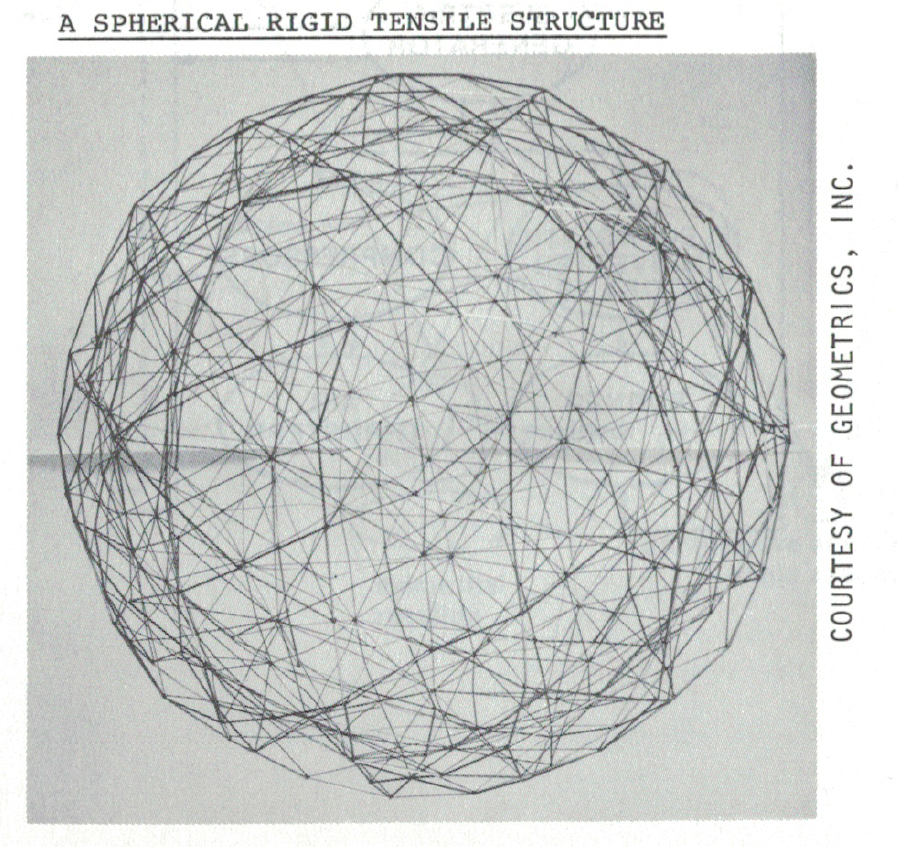

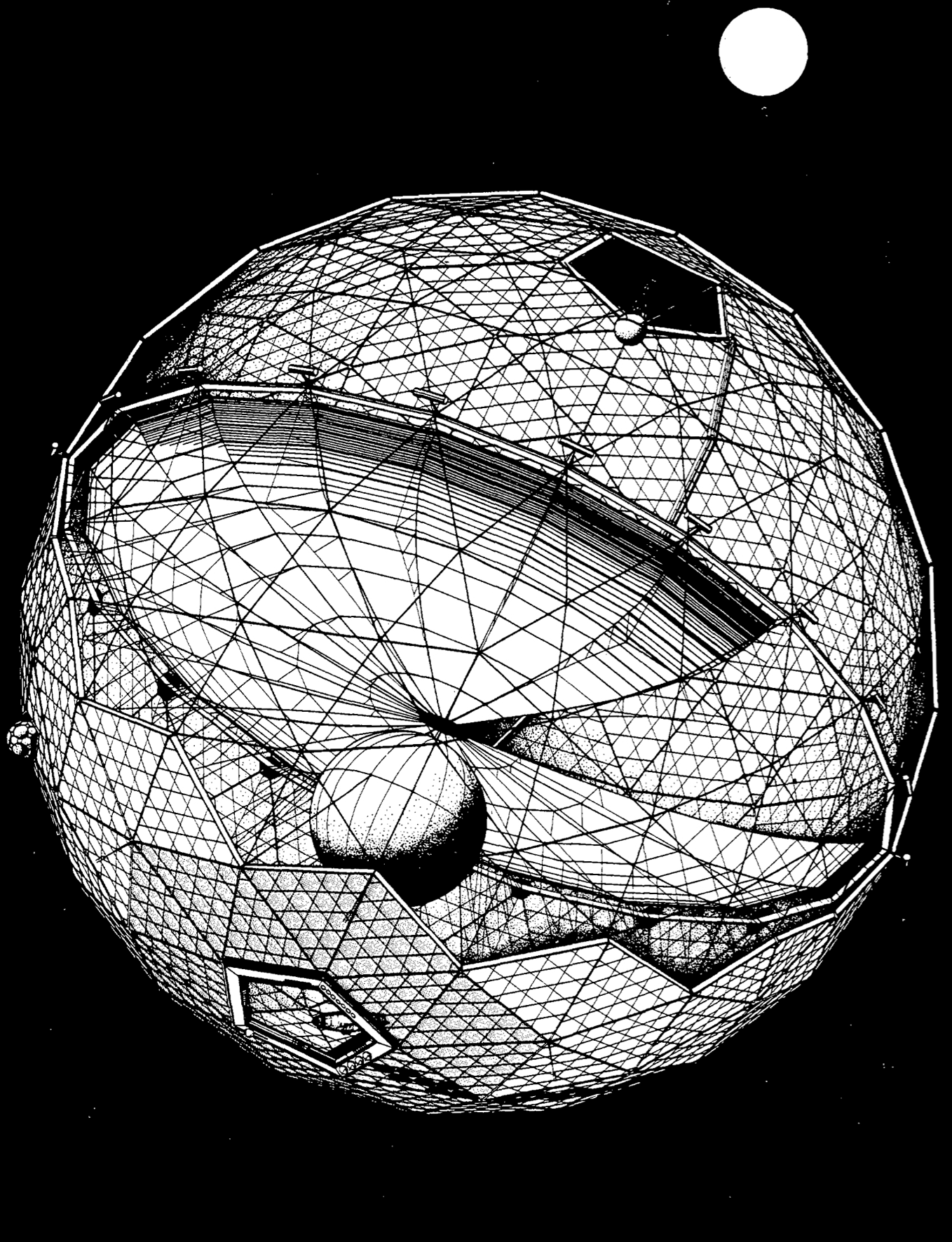

In the late 1970s, electrical engineer and physicist Ernest C. Okress picked up on the Cloud Nine idea for a concept he called the Solar Thermal Atmospheric Research Station (STARS). Fuller loaned him a 36-inch-wide tensegrity sphere[2], and assistance came from Okress’s Franklin Research Institute colleagues Robert K. Soberman and C.C. Von Statten. They performed concept-level studies demonstrating the feasibility of a mile-wide, rigid platform floating in the stratosphere, as well as outlining possible construction methods. In May of 1982, Science Digest reported that Okress and Soberman were developing a 650-foot-diameter STARS prototype called the Solar Powered Stratospheric Platform (SPSP), but this is the last press report I can find on STARS, and no more papers were published.

Franklin Research Institute Concept Art for STARS. From Gerard K. O’Neill’s 1981 book 2081

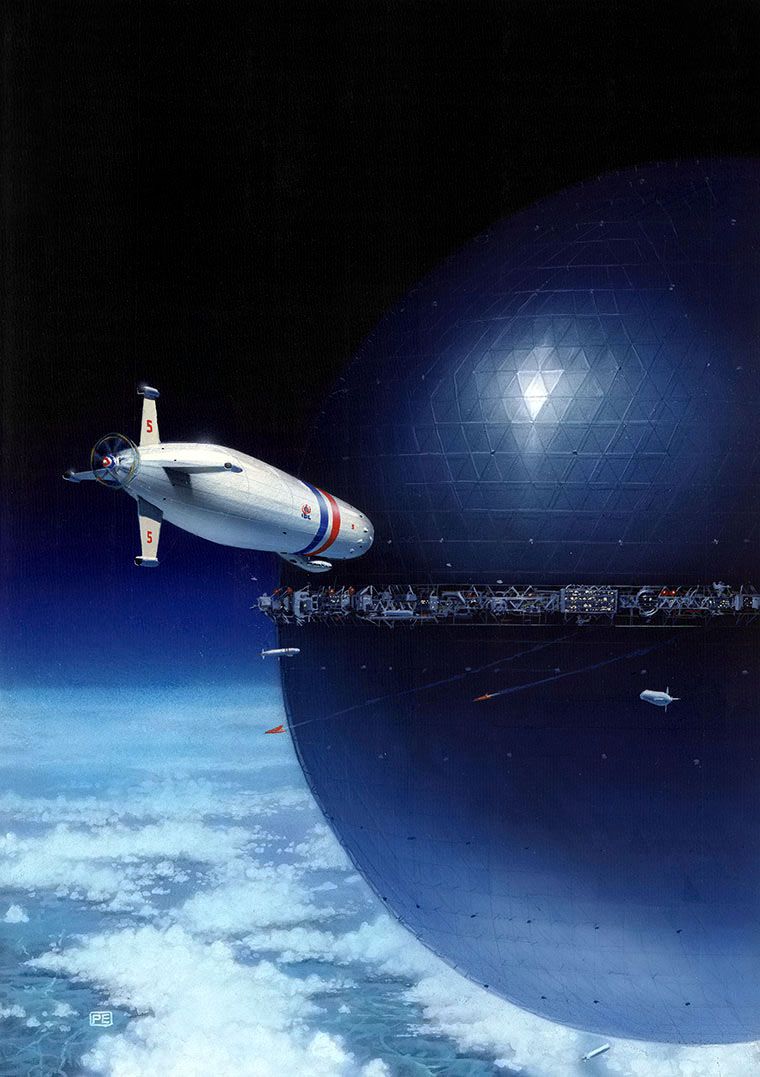

I discovered STARS while flipping through 2081, a tome of Gerard K. O’Neill’s predictions of the future, and this post collects the information and concept art I’ve uncovered since then. STARS also inspired the 1983 Poul Anderson novel Orion Shall Rise.

Peter Elson’s Cover for the 1987 edition of Poul Anderson’s Orion Shall Rise

the STARS concept

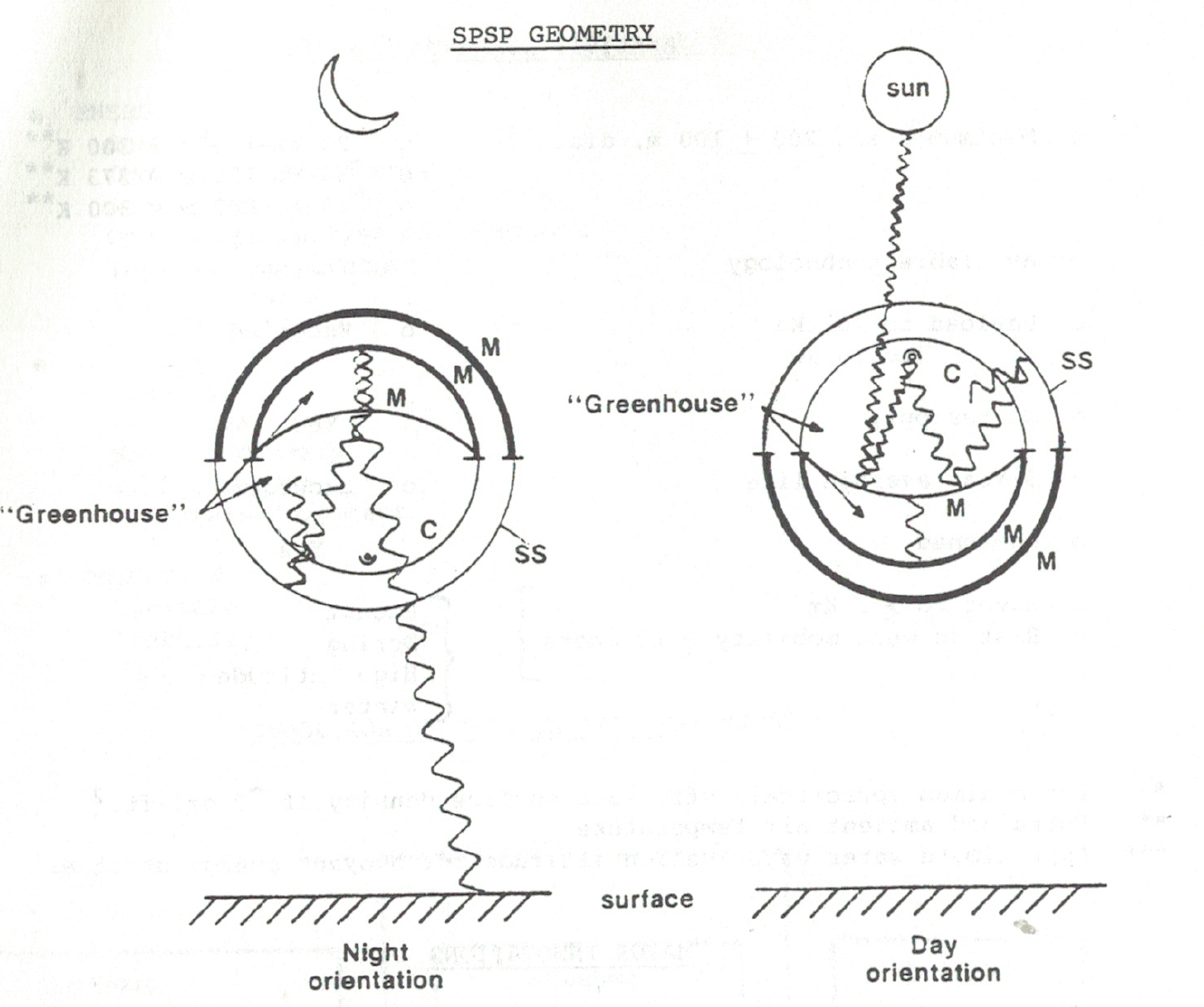

STARS is proposed as a double envelope balloon whose envelopes have an infrared reflective coating on their interior, similar to a double-layered greenhouse. Half of STARS is metallized and reflective to direct more sunlight to the solar energy absorption system. Various solar energy absorption systems are proposed, including photovoltaics, a solar-concentrating heat engine, suspended black carbon dust, and darkened water vapor.

In some scenarios, flipping the balloon upside down at night to minimize radiative heat loss is considered, although Okress and Soberman note that flipping the structure introduces substantial complexity.

Diagram of STARS and its day and night orientation

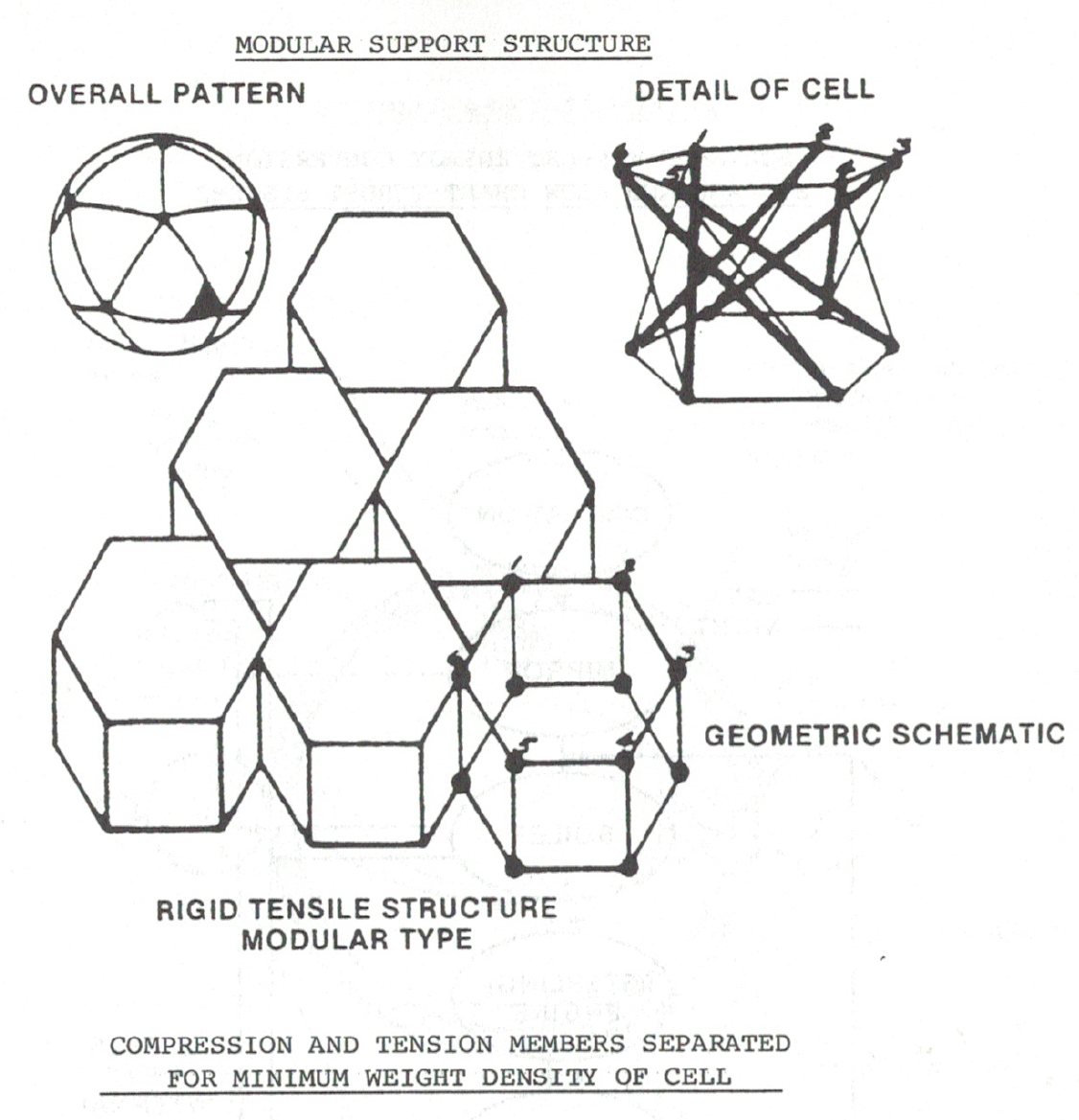

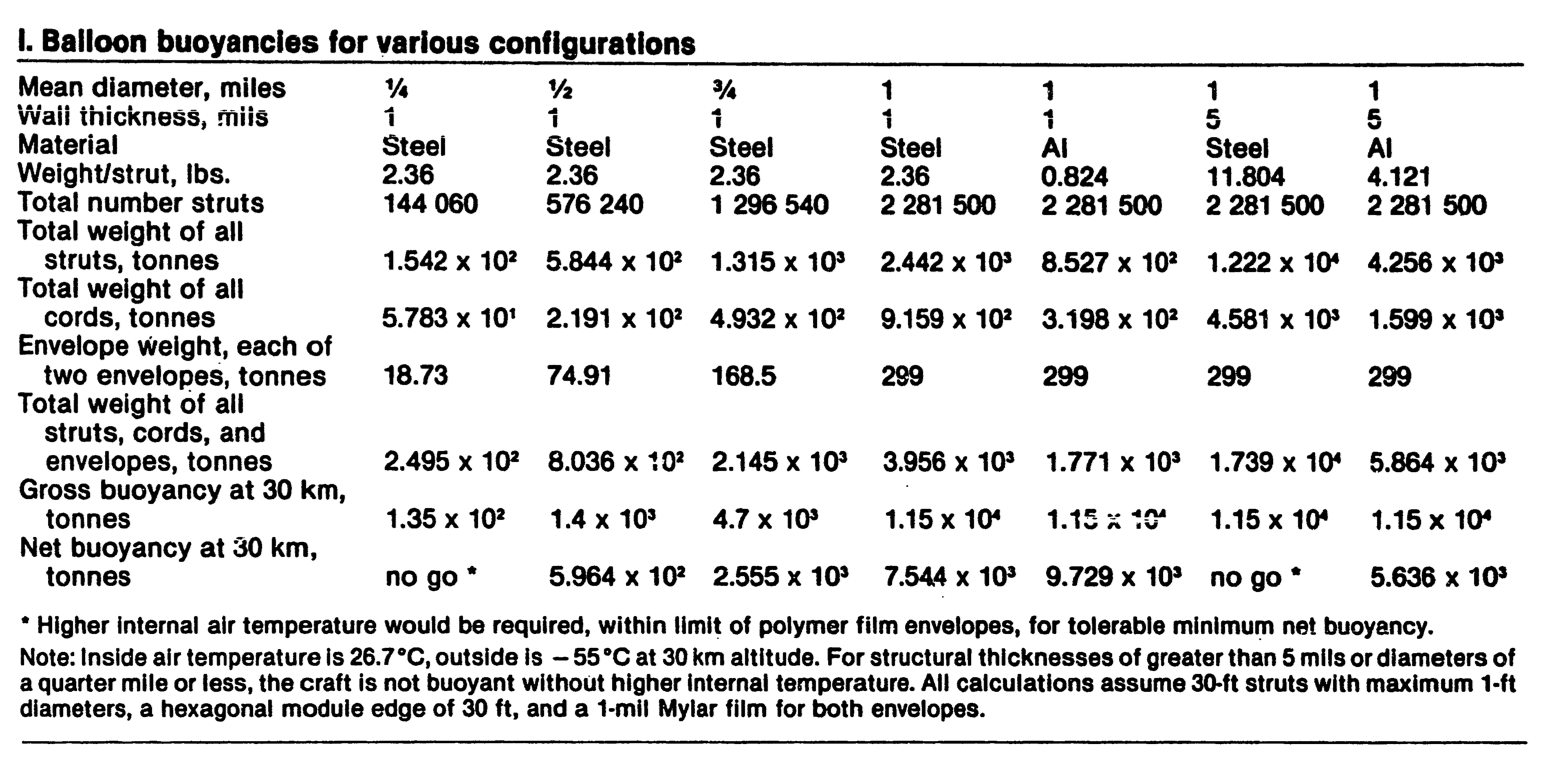

A modular, rigid, tensegrity structure gives the balloon a stiff surface necessary to resist wind gusts, as STARS is large enough to cross atmospheric layers and experience substantial wind shear. Modularity also allows the balloon to be repaired in flight and remain aloft indefinitely.

36-inch tensegrity geodesic loaned to the STARS team by Buckminster Fuller’s company, Geometrics, Inc.

Hexagonal tensegrity modules are interchangeable and collapsable, allowing them to be serviced, replaced, and assembled piecemeal. The envelope film is held in place along the perimeter cables of each module, so that it can be replaced. 1 mil (25.4 µm) thick polyester film is assumed in most configurations, with polyvinyl fluoride (Tedlar) for smaller, higher-temperature prototypes.

Proposed STARS modules and connection schema

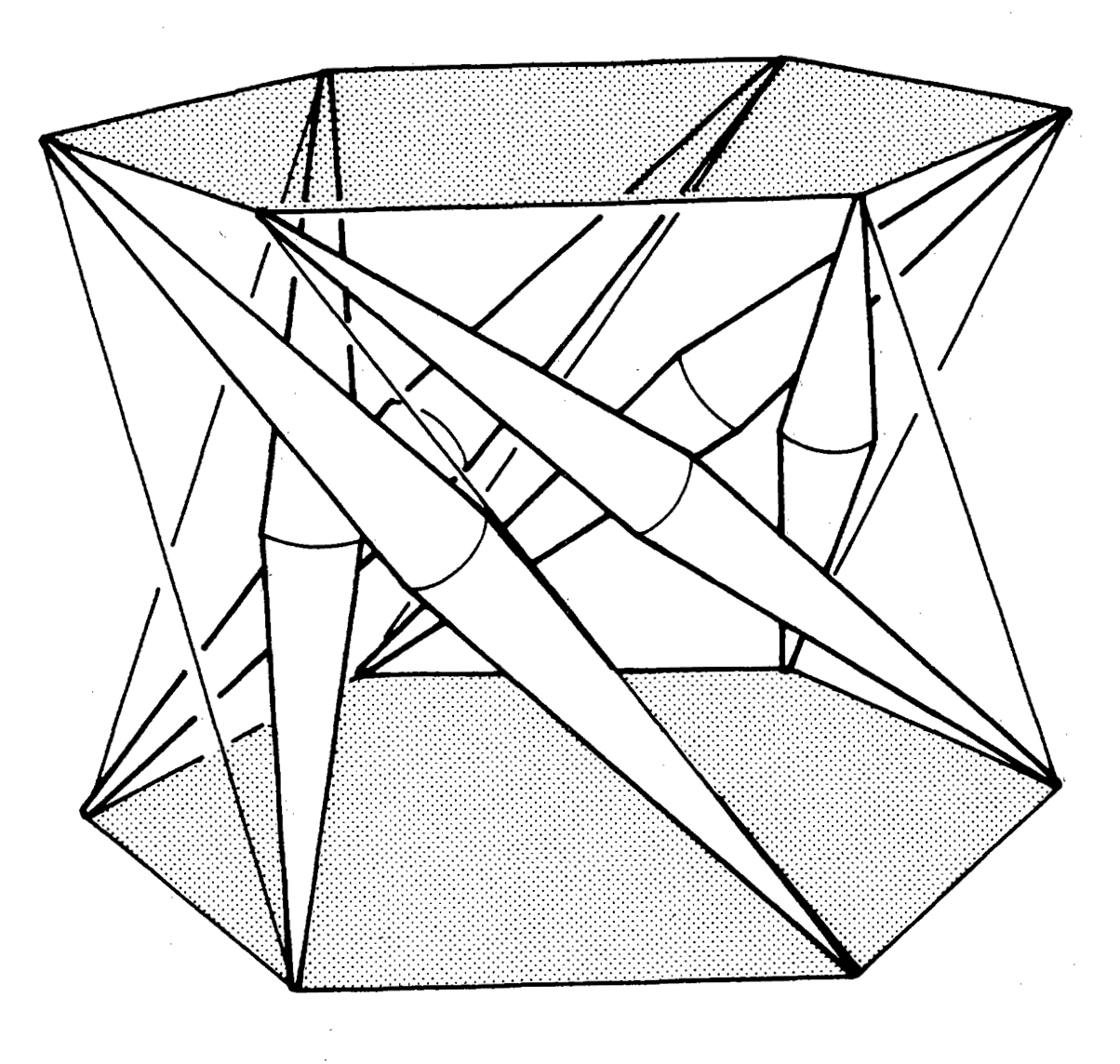

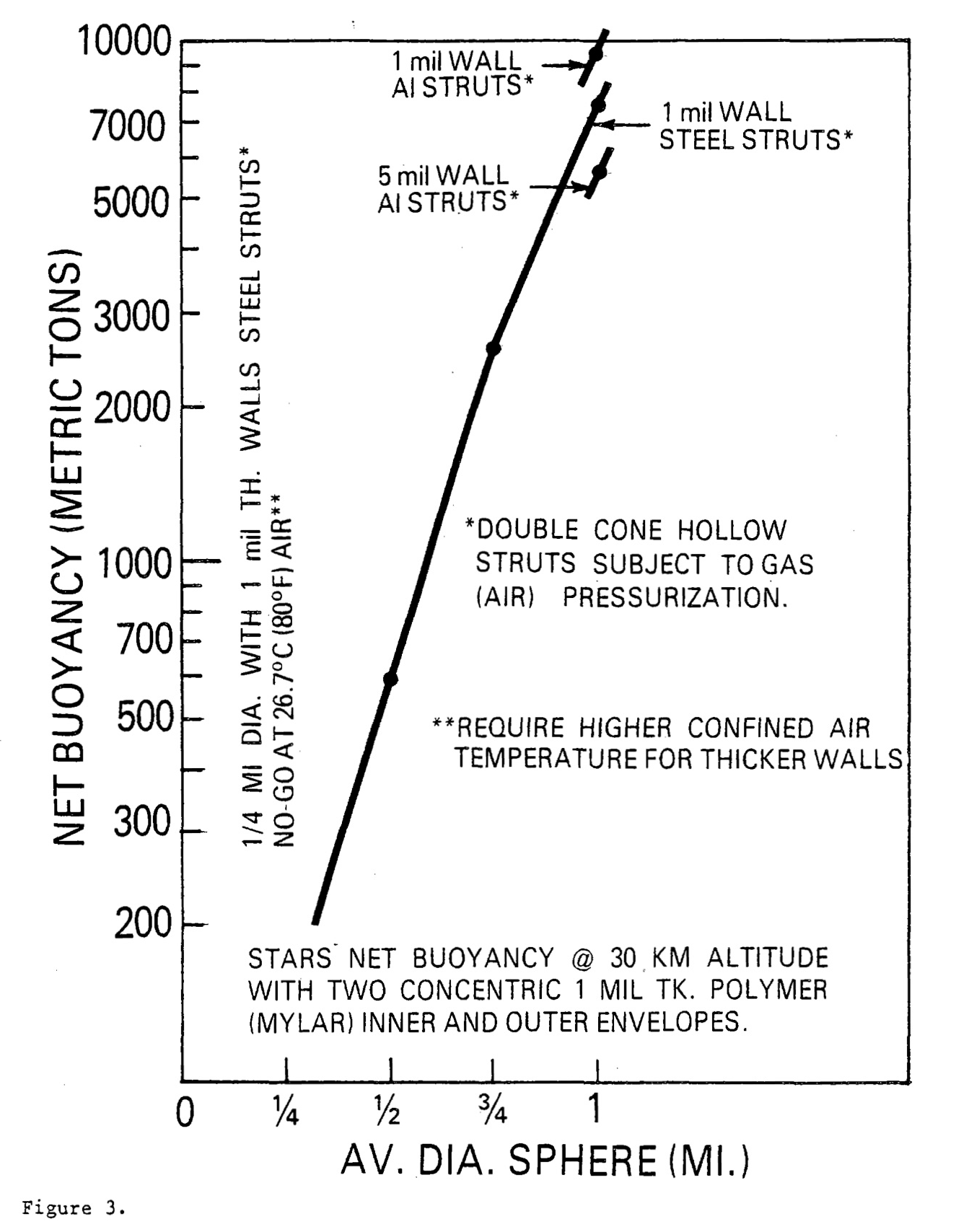

Each module’s rigid members are made from hollow double cones of thin (1 mil, 25.4 µm) steel or aluminum that are pressurized for rigidity.

Proposed STARS module detail

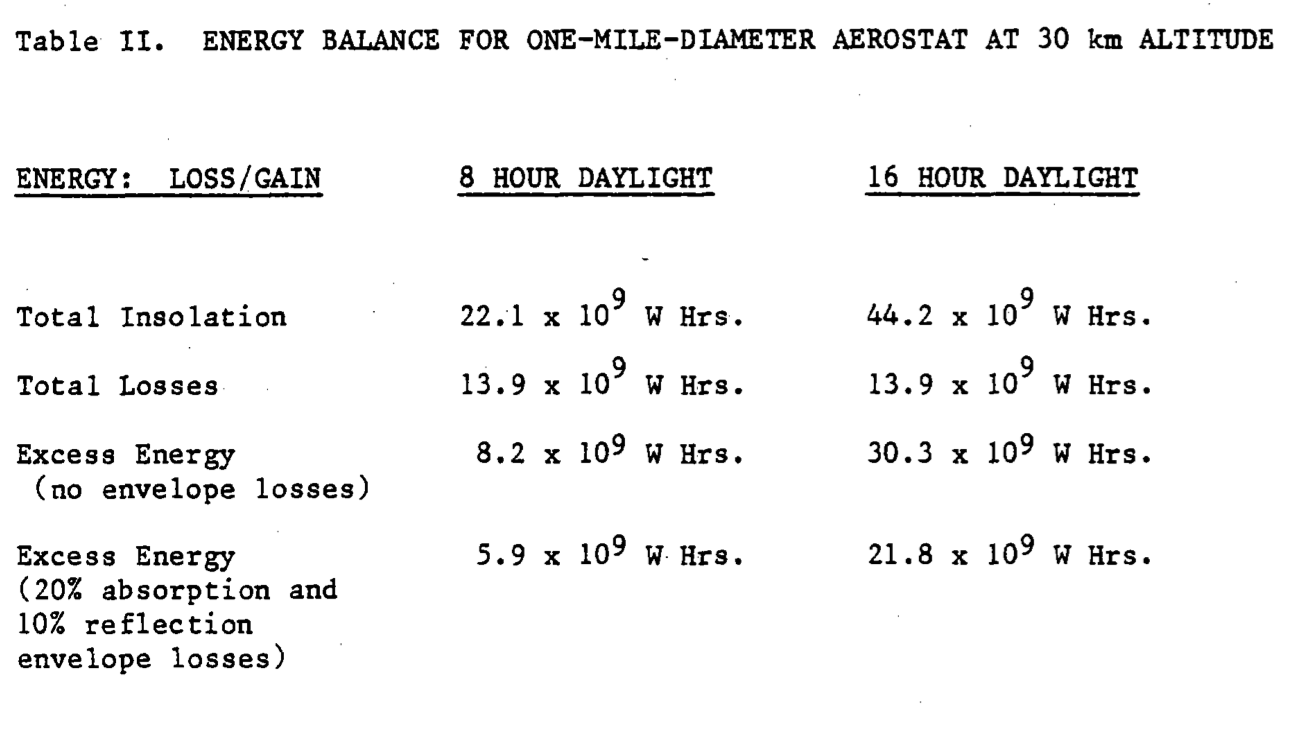

In order to avoid jet-dominated airspace, STARS flies above approximately 20 kilometers (about 65,000 feet) in air that is assumed to be -55 degrees Celsius. The interior of STARS is assumed to be 26.7 degrees, for a super temperature of 81.7 degrees Celsius. Plenty of excess energy is available to maintain this temperature from day to night.

Calculated excess energy

STARS’ rigid structure precludes changing size, and so STARS is a zero pressure design; interior pressure is the same as exterior pressure. Pumped air ballast is used to adjust to small changes in temperature. However, maintaining a constant interior temperature from day to night requires removing excess energy from the balloon during the day and adding energy at night to make up for losses.

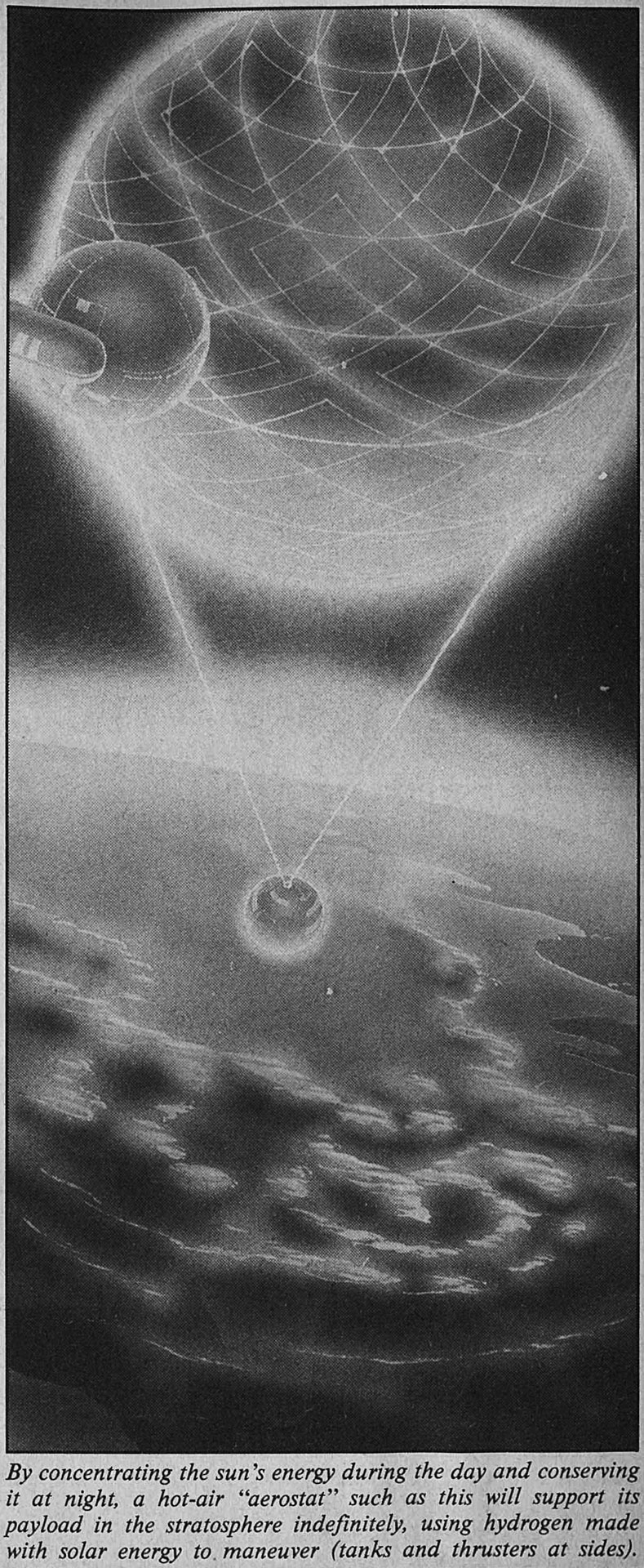

The most extensively explored system for balancing day to night energy needs is an onboard solar thermal power plant generating hydrogen. hydrogen is used for powered thrusters and to maintain interior temperature. Interestingly, hydrogen is not proposed as a lifting gas.

Diagram of solar-thermal power plant inside STARS

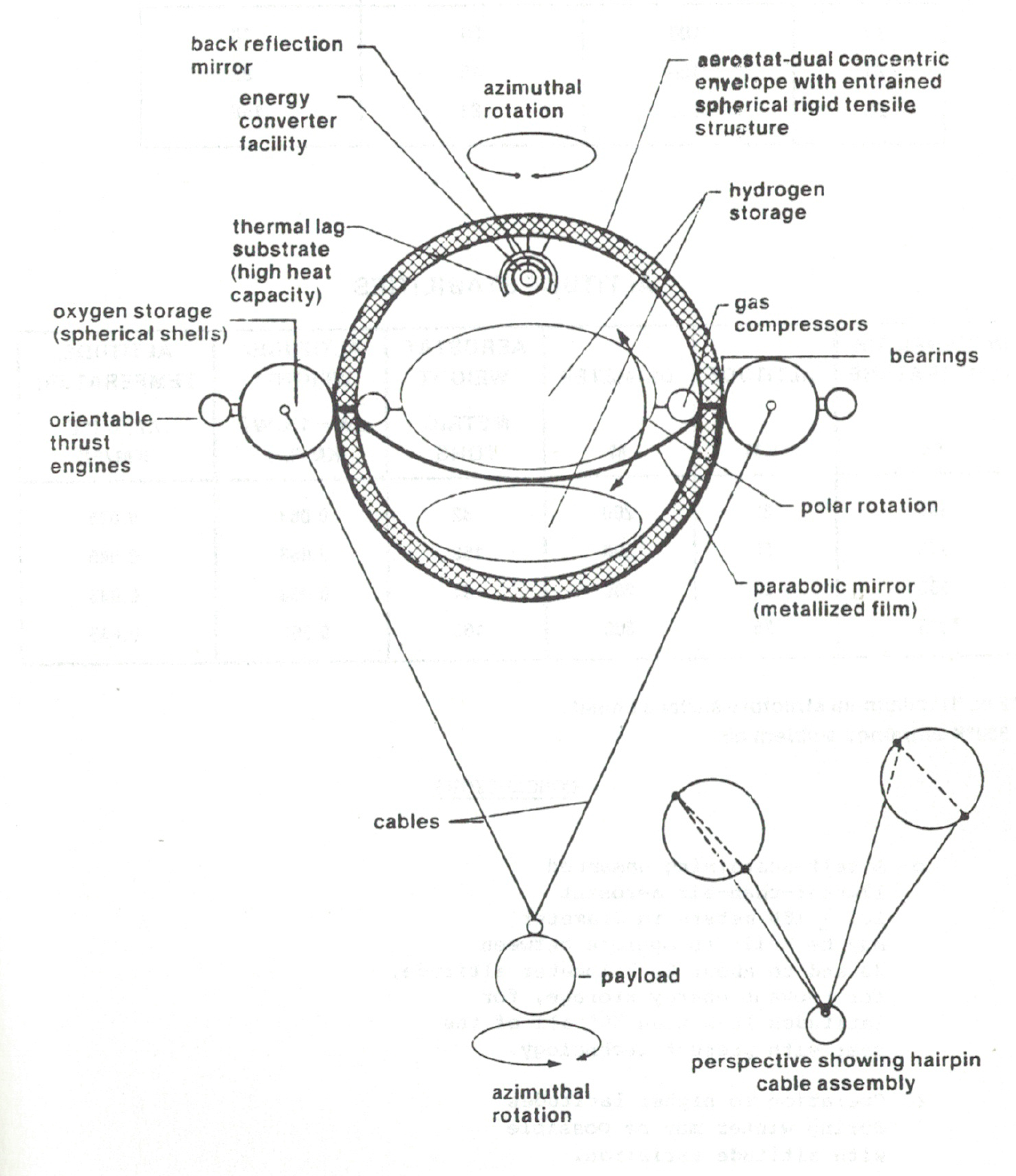

As an electrical engineer, Okress is interested in STARS functioning similarly to a space-based solar power station, transmitting excess energy to the ground using a microwave array. He also proposes replacing power storage by sending power to STARS at night to maintain altitude, either from the ground or from a space-based solar power station. This power station design for STARS receives the most effort in illustration.

Cutaway diagram of STARS as a solar-thermal power station. The dish in the middle is a parabolic reflector made from thin film, directing sunlight upwards towards another sphere representing the concentrator/heat engine. below the dish is a spherical balloon for pumped air ballast. structures around the balloon’s hemisphere represent thrusters to maintain position. The open bottom shows an airship shuttle leaving.

Although many components of this power station are speculative, STARS certainly has the excess lift to carry such a system.

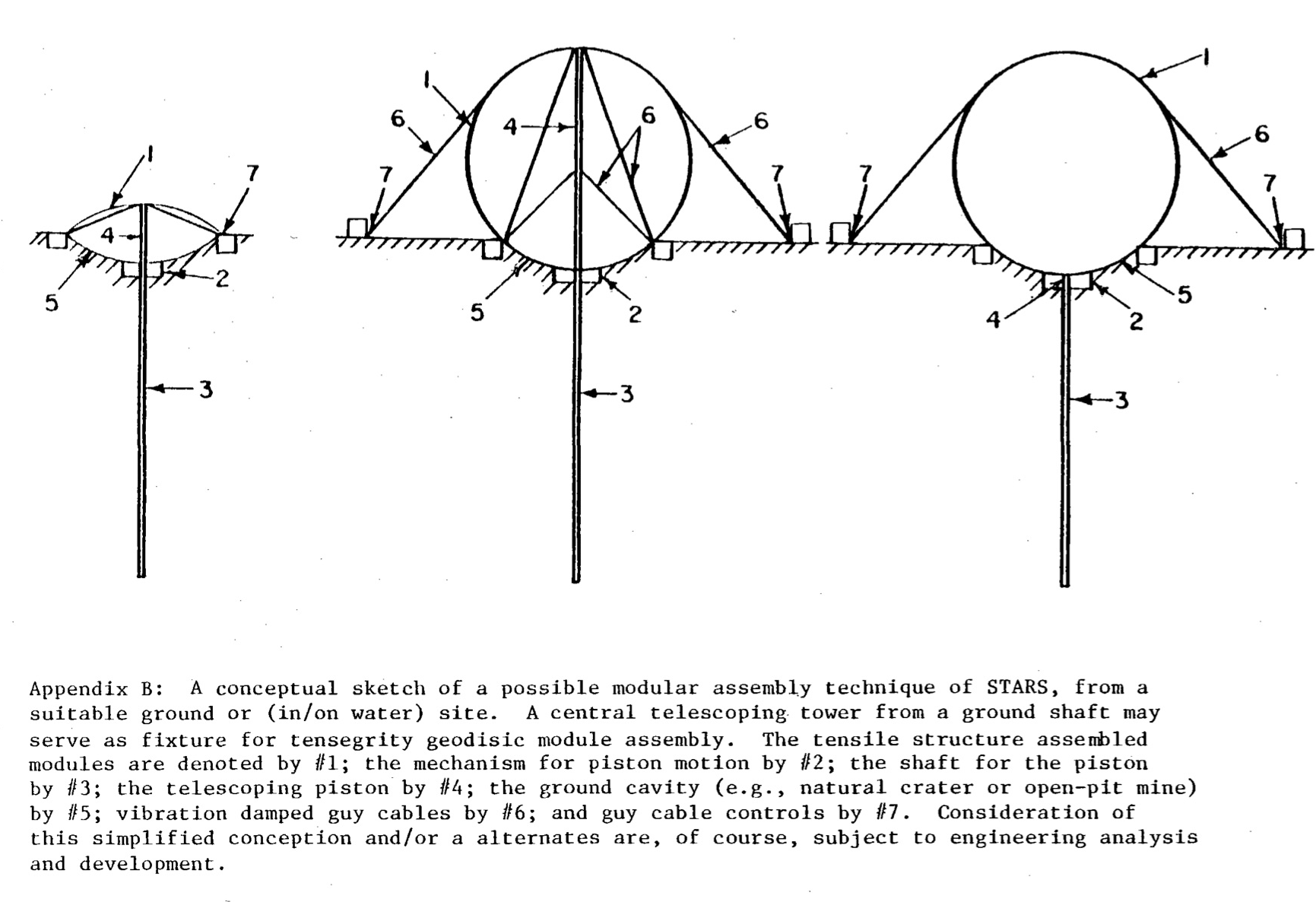

Three assembly methods are proposed: on the ground, over water, or in the upper atmosphere. Ground assembly requires a deep valley protected from the wind, and is based on elevating a mast structure in the center.

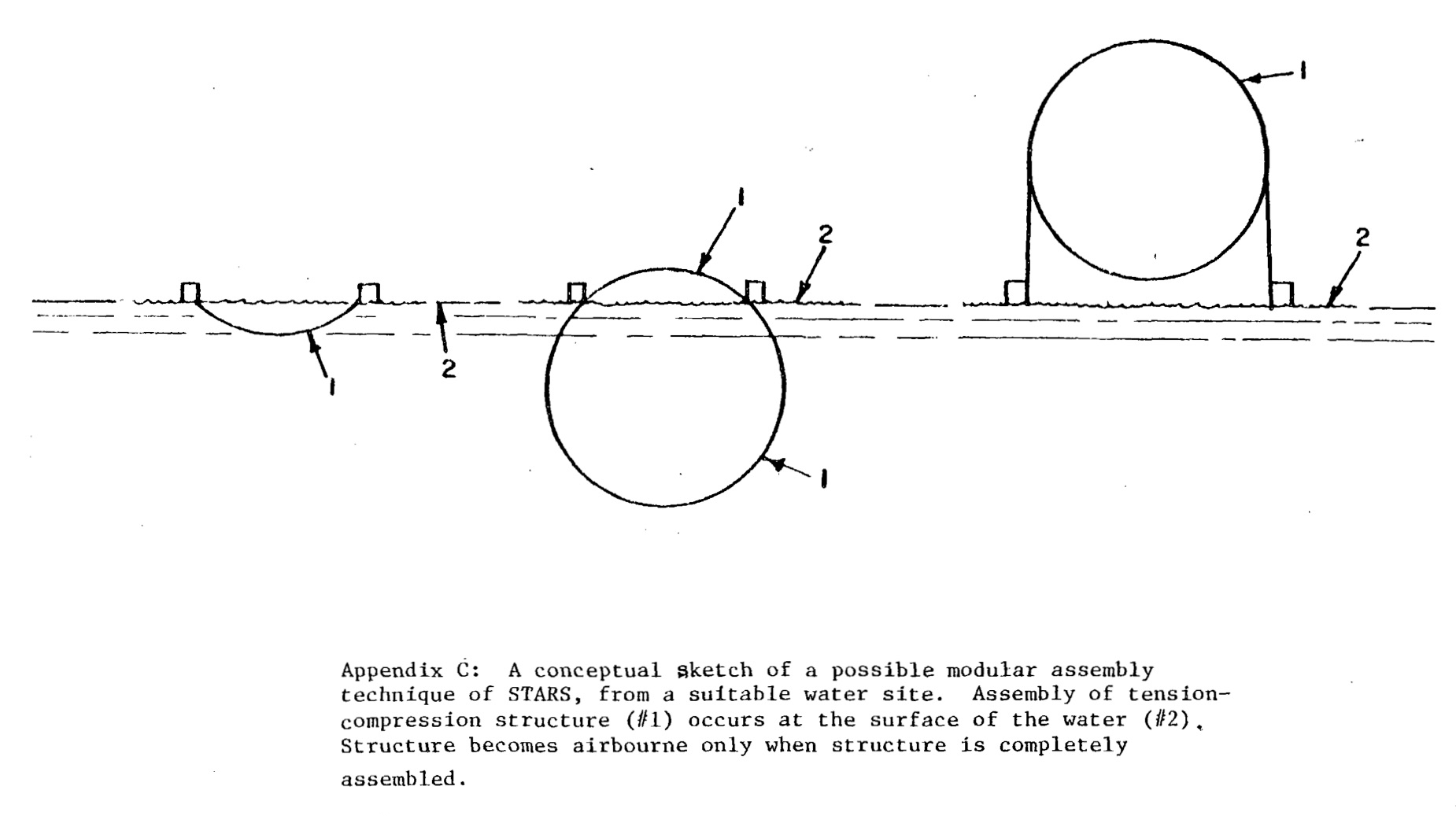

Assembly on the water would result in a submerged STARS that would then be floated and inflated, requiring an extremely deep bay or lake.

Okress proposes that STARS is best assembled in the upper atmosphere, although he does not explain how all those tons of material will stay aloft before fully enclosing a large volume of air. Okress’s reasoning for atmospheric assembly is that a super temperature necessary for take off will subject the balloon’s envelope to absolute temperatures that are too high. The polyester film specified for the balloon cannot handle such heat, and the alternatives suggested (PTFE, Tedlar) are problematic for cost and environmental reasons. However, polypropylene film is commercially available as greenhouse plastic and is structurally sound past the 108 degrees Celsius Okress imagines necessary [2].

my thoughts

Aircraft prototypes often fail catastrophically, and rigid lighter-than-air craft tend to have very large prototypes. Development is risky and high stakes. The smallest viable STARS prototype is an 80-ton, 200-meter-diameter structure made out of pressurized metal spikes[3]. If airborne megastructures ever come into existence, they will have to start from smaller, lower-stakes prototypes.

Smaller prototypes require an envelope with an order of magnitude lower mass per unit area than the 2 ounces per square foot of STARS [3]. An order of magnitude improvement seems feasible with contemporary composites. I’ve made rigid kites from Dyneema fabric and carbon fiber that come out around 0.05oz per square foot.

Several other technologies required for STARS are far more mature than they were in the early 1980s. Photovoltaics can replace the bulky solar thermal system. Shifting a balloon’s altitude to navigate precisely over long distances has recently been demonstrated by Loon, StratOAWL, and others, and could replace most of the thruster-based maneuvering STARS proposes.

The fossil fuel intensity and unknown environmental impacts of large-scale rocket launches make a STARS-like platform a desirable replacement for satellite systems. New technology makes STARS more possible, and floating in the upper atmosphere rather than circling the earth should reduce costs per kilogram by at least three orders of magnitude[6].

However, there remain no high-altitude airships to reach, resupply, and maintain a giant upper-atmospheric structure. The last attempt at constructing such a craft, Lockheed-Martin’s HALE-D, was canceled. Like STARS, each of those airship prototypes will be big, high stakes, and risky.

Rockets and jets are mature, incumbent technologies supported by a large number of professionals, educational programs, established infrastructure, supply networks, and a huge installed base of equipment, creating path dependency. Until the aerospace industry is forced to reckon with the intense environmental impacts of burning massive amounts of fuel in the upper atmosphere, new lighter-than-air craft will remain on the industry’s fringes.

situating STARS within solar ballooning

Research into STARS began after the first solar hot air balloon flights of Tracey Barnes (1973) and Dominic Michaelis, who flew over the English Channel in 1984. STARS also ran concurrently with beginning of the CNES Montgolfière Infrarouge project that flew balloons heated by the infrared flux of earth. These balloons were half-silvered and made from mylar, like the STARS concept.

Since at least 2010, Aerocene artist and solar aeronaut Tomás Saraceno has been using half-reflective spherical balloons as representations of floating habitat concepts.

misguided concept art

Someone at Science Digest commissioned this realistic illustration of a STARS diagram. It’s kind of ridiculous:

bibliography

art:

I’m pretty sure there is more concept art out there. Unfortunately, the Franklin Research Institute was dissolved in the mid-1980s, and the Franklin Institute does not have records from the Franklin Research Institute. What records remain are at the University of Delaware and Swarthmore College. Librarians at both institutions were unable to identify further info on this project.

Fuller, R. Buckminster and Shoji Sadao. 1960. Project for Floating Cloud Structures (Cloud Nine). Stanford: Stanford University Libraries Department of Special Collections, Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller.

Elson, Peter. 1987 edition. Orion Shall Rise. Cover for book of the same name by Poul Anderson, originally published 1983. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Worpole. Ian. 1982. Dirigible at the Edge of Space. Science Digest, Volume 90, May 23, 1982. Des Moines: Hearst Corporation.

O’Neill, Gerard K. 1981. 2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future. New York: Simon & Schuster.

papers referenced:

The core information about STARS is contained in the 1980 presentation to the Society of Allied Weight Engineers.

[1] Okress, Ernest C. 1978. The Franklin Institute has High Hopes for Its Big Balloon. IEEE Spectrum 0018-935/1200-0041$00.75, December, 1978. New York: Institute of Electrical & Electronics Engineers.

[2] Okress, Ernest C. and Robert K. Soberman. 1980. Solar Thermal Research Station (STARS). Presentation at the 39th Annual Conference of the Society of Allied Weight Engineers. SAWE Paper No. 1376. Los Angeles: Society of Allied Weight Engineers, Inc.

[3] Okress, Ernest C. and Robert K. Soberman. 1980. Solar Powered Stratospheric Platform (SPSP). Proceedings of the Third Miami International Conference on Alternative Energy Sources, December 15-17, 1980. Volume 3, Solar Energy 3. ed. Veziroğlu, Nejat T. Washington (DC): Hemisphere Publishing Corporation.

[4] Okress, Ernest C. and Robert K. Soberman. 1981. A Stratospheric Platform - Substantial Advances of the STARS Project. Presentation at the 40th Annual Conference of the Society of Allied Weight Engineers. SAWE Paper No. 1436. Los Angeles: Society of Allied Weight Engineers, Inc.

[5] Okress, Ernest C. and Robert K. Soberman. 1981. Solar Powered Stratospheric Platform Space Manufacturing IV : Proceedings of the fifth Princeton/American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Conference, May 18-21, 1981. Washington (DC): American Institute of Aeronautics & Astronautics.

[6] Yajima, Nobuyuki, Naoki Izutsu, Takeshi Imamura, and Toyoo Abe. 2004. Scientific Ballooning: Technology and Applications of Exploration Balloons Floating in the Stratosphere and the Atmospheres of Other Planets. New York: Springer.

further references not found:

Okress, Ernest C. and Robert K. Soberman. 1980. Paper IAF 79-F-35, Proceedings of the XXXth International Astronautic Federation Congress, September 21, 1979. Munich: Pergamon Press.

Okress, Ernest C., Robert K. Soberman, and Von Stretten. 1980. The Construction Specifier, Vol. 3 No. 1. January, 1980. Alexandria (VA): Construction Specifications Institute.